Hi

It’s been an extraordinary year in so many ways, and investment markets during November were no exception. The ASX had its best month in over 30 years, following similar strong gains from US and global markets. Equity markets, and each of our funds, pretty much provided one year’s worth of returns in one month. There are two ways of thinking about this. The first is that this is just part of the catch up and recovery from the market selloff earlier in the year. The second is that this is an explosion of exuberance and investors are showing a disturbing level of risk complacency.

We can make an equally compelling case for both alternatives. For example, the US equity market, which is at all time highs, is significantly more expensive than most other markets.

Australia on the other hand, remains below its February highs, and appears more reasonably valued. There are huge tail winds for equity markets, in the form of low or zero interest rates and significant government stimulus. But no-one really knows the true unemployment figure and economic damage, because it’s being masked by jobkeeper, jobseeker and a raft of other temporary measures.

The good news is that while many assets are well overvalued, we continue to find plenty of investments that appear cheaper than average. That means we’re still excited about the potential for all of our funds. If you’re interested, I would encourage you to view our November Webinar (see link below). We discussed the divergence in investment conditions, as well as how our funds are positioned, some of our top fund and LIC holdings and where we’re seeing opportunities. You can also read on for our monthly fund reports, links to some exceptional articles on the value vs growth debate, and other stuff we found interesting.

If you’d like to invest with us this month, you’ve got until Thursday 24 December to apply for the Affluence Investment Fund or Affluence Small Company Fund. Affluence LIC Fund applications must be completed by 31 December. As always, go to our website and click the “Invest Now” button to apply online or download application/withdrawal forms. If you have any questions, simply reply to this email or give us a call at any time.

Thanks for reading and for your continued support over the past year. We wish you all the best for the festive season and a Happy New Year.

Daryl, Greg and the Affluence Team

Affluence Fund Reports & News

Affluence Investment Fund Report

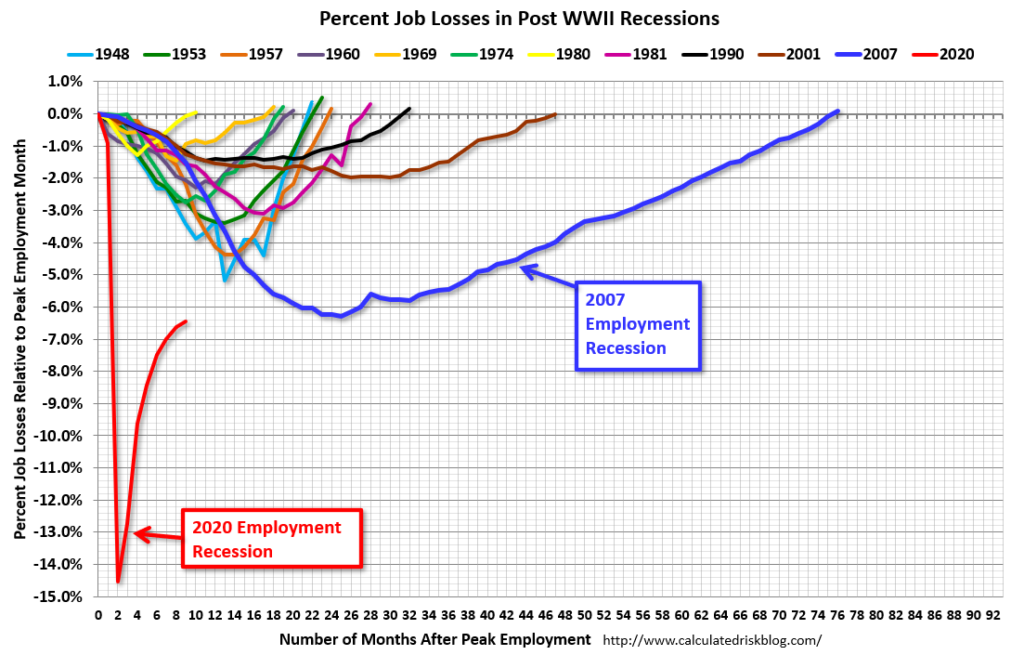

The Fund returned 5.9% in November. Since commencing in 2014, returns of 8.3% per annum have exceeded the ASX200. Distributions have averaged 6.7% per

annum, paid monthly. See the report for more detail including our top holdings.

Affluence LIC Fund Report

The Fund returned 9.7% in November. Since commencing in 2016, returns of 12.7% per annum have exceeded the ASX200. Distributions have averaged 7.4% per annum, paid quarterly. See the report for more detail including our top holdings.

Affluence Small Company Fund Report

The Fund returned 9.6% in November and has outperformed the ASX Small Ordinaries index by 15.7% over the past year. If you’re a wholesale investor looking for out of favour small cap value, you’re going to find this fund very interesting.

Unlock a replay of our Webinar

Last month we provided an update on how our funds are positioned, including some of our top fund and LIC holdings. We also explained where we’re seeing opportunities in this market and answered your questions. Access the replay below.

All Weather Fund, Monthly Distributions

The Affluence Investment Fund gives you access to a portfolio of vastly diversified assets and investment styles through a range of exceptional fund managers chosen by us. The result is an all-weather portfolio that can deliver in differing market conditions. Many of the managers in the Affluence Investment Fund are closed to new investors, only available to wholesale clients or have high minimum investment amounts.

The Affluence Investment Fund targets a minimum distribution rate of 5% per annum. Over the life of the Fund, cash distributions have averaged 6.7% per annum. Distributions are paid 10 days after the end of each month, or you can reinvest and receive additional units.

Returns shown above exclude franking credits received from investments and passed through in full at the end of each tax year. These have typically averaged 0.4% to 0.5% per annum.

Other Interesting Stuff

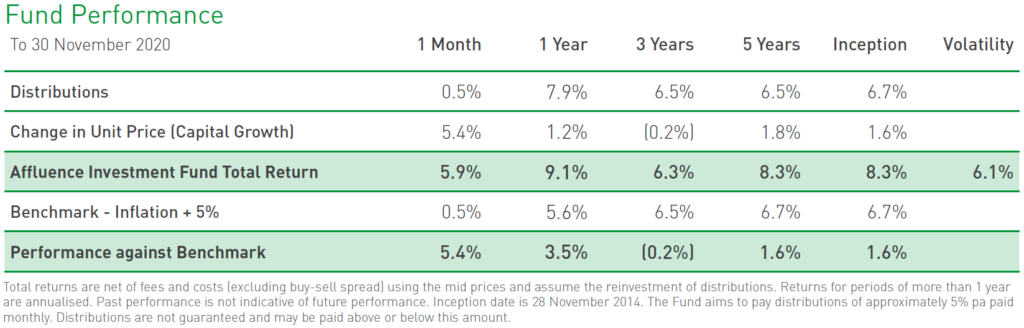

Chart of the month.Below are US job losses from the start of every employment recession since World War II, in percentage terms. The current employment recession is by far the worst. Current post recovery job losses are still worse than the worst point in the “Great Recession”, which was the previous record holder. And the recovery is showing signs of slowing markedly.

Compare that data to US stock markets, which are at all time highs and well above where they were at the start of the year. That makes no sense.

This month in (financial) history:

During the great depression, Charles B. Darrow came up with a board game he thought was pretty cool. In 1934, he presented the game to executives at Parker Brothers and was rejected.

A year later, after he sold 5,000 homemade copies, Parker Brothers snapped it up.

The game was Monopoly. However, after buying the rights from old Charlie, Parker Brothers learned that he was not the sole inventor of the game. They eventually also bought the rights

to the original inventors’ version for an extra $500. It turned out to be not a bad investment.

Since being patented by Parker Brothers 85 years ago in December 1935, Monopoly has been translated into 37 languages and evolved into over 200 licensed and localised editions for 103 countries across the world. Over 250 million sets of Monopoly have been sold since its invention and the game has been played by over half a billion people. The original version of the game was based on the streets of Atlantic City, New Jersey.

By the way, in 1941, the British Secret Intelligence Service had a special edition created. It was distributed to World War II prisoners of war by fake charity organisations. Hidden inside these games were maps, compasses, real money, and other objects useful for escaping. British historians estimate that the MacGyvered Monopoly boards could have helped thousands of captured soldiers escape from their prison camps. Think about that, nexttime you turn over a “Get Out of Jail Free” card.

Quote of the month:

“From 2000 – 2013 MSFT [Microsoft] grew their revenues by 350%, however an investor who bought MSFT in 2000 made 0% from capital appreciation over the period to 2013, despite tremendous growth in the company. In our view, asymmetric investing does not entail buying growth at any price.”

Kenny Arnott, Arnott Opportunities Fund. It’s fair to say that most growth investors are not thinking this way right now.

Holiday reading:

Ever since we started Affluence, we’ve been hamstrung by a trend that has gone on a lot longer than many (including us) thought probable. Returns from value investing have lagged those from growth investing. By a lot. In fact, after more than a decade of disappointing performance, value stocks experienced probably their worst 12-month performance in history to the end of October this year.

The trend finally started to change in November. We firmly believe that over the next few years, value will outperform growth by a substantial amount. And we would encourage everyone to consider getting some exposure to funds and managers with a value focus.

We’ve had plans for a while now to write a long piece about why value investing is not dead, and why it should be a focus for anyone looking to add some sizzle to their portfolio. But over the last few weeks, we’ve come across several exceptional articles that explain the value proposition much better than we could. They explore many of the reasons why value investing is currently perceived to be an inferior strategy, and explain why they are exaggerated, misconstrued or just plain wrong.

Here they are, in no particular order.

Market inefficiency, liquidity flywheels, asset class arbitrage

Lyall Taylor, value investor and author of the excellent LT3000 blog, explains why the efficient market hypothesis doesn’t work (at least not efficiently), and how liquidity flywheels lead to cyclical distortions in asset prices. This means radically different valuations can emerge for the same assets, depending on how they are packaged. If you are prepared to stomach some volatility, you can profit handsomely from these divergences.

Unravelling value’s decade-long underperformance (and imminent resurgence)

This follow up article provides insights into what has driven the value vs growth trade, and why that might be about to change.

Tonight we leave the party like its 1999

The first of two articles from the mean reversion experts at GMO. This one, written in early November, discusses the eerie parallels between today’s markets and 1999. Back then, GMO was looking stupid for still believing that valuations mattered and the gravitational pull of mean reversion would eventually work. They see ominously similar market phenomenon today.

In the latest quarterly letter, GMO’s Ben Inker explains why value is cheap from a range of different angles. He concludes that if even if value stocks were to continue trading at current spreads to the market, they would beat the market if they experienced the same relative fundamental performance as they have over the past 14 years. In other words, value stocks don’t even need to mean revert to outperform.

He also explains why GMO believe growth stocks have entered a bubble similar to the one in 2000.

Is value investing really dead?

Nick Kirrage from Schroders compares the value vs growth divergence at end of the dotcom boom in 2000, to now, and explains what happened in 2001.

Finally, if you have an hour to spare, this video featuring our perennial favourite, Howard Marks, is definitely worth watching. Start from about the 6 minute mark. Spoiler alert – he is not sure where markets are either. He suspects the US economy really is recovering, but equity markets have raced ahead of fundamentals. At around 34:20 he provides his thoughts on growth vs value. His definition of growth and value, we think, are brilliant.

Incidentally, if you are looking to boost your exposure to value, you can access a wide range of value investing funds (along with many other things) through either our Affluence Investment Fund or, if you’re a whoesale investor, our Affluence Small Company Fund.

Did you know?:

There’s a standard way to understand the relative danger of any activity. A micromort is a unit of risk defined as one-in-a-million chance of death. For example, skydiving is 8 micromorts per jump but running a marathon is 26 micromorts. From this, you could conclude that exercise is bad for you!

Just being alive averages about 24 micromorts per day (but more when you are very young and as you age). The “safest” age is 10 years old.

Travel micromorts vary depending on the mode. For example, 1 micromort is equal to travelling:

- 10 km by motorbike.

- 16 km by bicycle.

- 27 km by walking.

- 370 km by car.

- 1,600 km by plane.

- 9,656 km by train.

Or looked at another way, motorbikes are about 1,000 times as dangerous as trains.

Video of the month:

Comedic genius is pointing out the absurdity of everyday things you normally take for granted. We give you Jimmy Rees, as the guy who decides packaging. If you like that, there’s loads more out there from Australia’s new king of comedy.

It’s not what you think:

A lengthy and bitter election campaign that was sullied by a voter fraud scandal came to an unlikely end in November. No, it’s not the US election. It’s the NZ bird of the year competition, when a flightless and nocturnal parrot stunned pundits to claim an upset victory.

Read all about it here.

And finally:

The long term cost of all this Government spending…

Media and Presentations

AFR journalist Tony Boyd named our Affluence Small Company Fund one of the five best value funds over 12 months in this article.

We regularly present to investment groups on various topics including our Affluence Funds, how we choose great fund managers, LICs and the investment environment.

If you would like to meet with us or have us speak with your investment group, get in touch.

Are you an Affluence Member?

We’ve spent hundreds of hours looking for Australia’s best Fund Managers and LICs.

Click below to register as an Affluence Member and see the results of all our hard work! Access our Affluence Fund portfolios and profiles of managers we invest with.

Thinking about Investing with us?

If you would like to learn more about our Funds, or invest with us, the buttons below will take you to the right places.

If you have a question, you can email or call using the details below. Alternatively, click on the ‘contact us’ button, fill out the contact form on our website and we will be in touch with you as soon as we can.

P: 1300 233 583 | E: invest@affluencefunds.com.au | W: affluencefunds.com.au

This information has been prepared by Affluence Funds Management Limited ABN 68 604 406 297 AFS licence no. 475940 (Affluence) as general information only. It does not purport to be complete and it does not take into account your investment objectives, financial situation or needs. Prospective investors in any Affluence Fund should consider those matters and read the Product Disclosure Statement (PDS) or Information Memorandum (IM) offering units in the relevant Affluence Fund before making an investment decision. The PDS or IM for each Affluence Fund contain important notices and disclaimers and important information about the relevant offer.

As with all investments, an investment in any Affluence Fund is subject to risks. If these risks eventuate, they may result in a reduction in the value of your investment and/or a reduction or cessation of distributions. Distributions are not guaranteed, nor is the return of your capital. Past performance is not indicative of future performance. The value of your investment will go up and down over time, returns from each fund will vary over time, future returns may differ from past returns, and returns are not guaranteed. All of this means that there is always the chance that you could lose money on an investment. As set out in the PDS or IM for each Affluence Fund, key risks include concentration risk, economic and market risk, legal and regulatory risk, manager and key person risk, liquidity risk, leverage risk and currency risk. Affluence aims, where possible, to actively manage risks. However, some risks are outside our control.

This information and the information in the PDS or IM is not a recommendation by Affluence or any of its officers, employees, agents or advisers and potential investors are encouraged to obtain independent expert advice before any investment decision.

The Morningstar Rating™ is an assessment of a fund’s past performance – based on both return and risk – which shows how similar investments compare with their competitors. A high rating alone is insufficient basis for an investment decision. © 2019 Morningstar, Inc. All rights reserved. Neither Morningstar, its affiliates, nor the content providers guarantee the data or content contained herein to be accurate, complete or timely nor will they have any liability for its use or distribution. Any general advice or ‘class service’ have been prepared by Morningstar Australasia Pty Ltd (ABN: 95 090 665 544, AFSL: 240892) and/or Morningstar Research Ltd, subsidiaries of Morningstar, Inc, without reference to your objectives, financial situation or needs. Refer to our Financial Services Guide (FSG) for more information at www.morningstar.com.au/s/fsg.pdf.

You should consider the advice in light of these matters and if applicable, the relevant Product Disclosure Statement before making any decision to invest. Our publications, ratings and products should be viewed as an additional investment resource, not as your sole source of information. Past performance does not necessarily indicate a financial product’s future performance. To obtain advice tailored to your situation, contact a professional financial adviser.